1.

The nurses have tied up my mother’s hair into a knot. Permed curls straightened, she looks old, lined, worn out. I arrive late at the ICU after the children’s homework is finished, the littlest one asleep. The washed-out green walls here are shaded by blue lights which reflect waves like the sea in Jamaica. When my mother and I walked on the beach there years ago, transparent fish swam over our feet and shadows of bougainvillea branches brushed our shoulders as we played with my children in the shallow water. Now I have to drive for an hour through highway traffic to sit by her bed and hold her hand.

I talk to her closed eyes about my day, the rain, what her grandchildren are doing in school. The nurses ignore me. I know none of them by name. Maybe they don’t even see me. Maybe they associate me with my father and think that I am as uncaring as he appears to be. He hates hospitals and makes the ten-minute journey twice a day to stay for half an hour before brushing away the smell of disinfectant and going home, telling himself that this place has nothing to do with him. Death mustn’t touch him. She lies alone most of the time.

At first I tell my father about my midnight visits and how I drive home into the next morning as the sun is starting to lighten the sky, but he is angry. He shouts that I should visit him at the same time. How can I be so close and not call in? What kind of a daughter am I to ignore him in these, his difficult hours? Dutifully obeying, I become a daughter split into two pieces and mothering teenagers at home fragments me even more. So I stop talking about my visits and ignore the highway exit to his street as I drive north with the sound of my dying mother’s monitored heartbeat in my head.

Then my father accuses me of not caring about her, of only bothering to visit her once a week, on Sundays when I do take the exit to his house and hear how terribly hard his life is now that she is ill. He tells me I am selfish. I keep quiet about how selfish I really am, selfish of my time alone with her.

2.

I remember hiding under the kitchen table wrapped up in her arms while airplanes flew over our house, their German pilots trying to find a trainload full of soldiers that I knew was stopped on the railway line behind our garden fence. And I remember sitting on the grass playing with little cardboard letters, making words and sentences in the shadow of the sumac tree, brushing away ants and red berries. My mother taught me to read that way, giving me a voice, telling me that books would open up magic worlds and I believed her.

When I was ill, she tucked me into sweet-smelling sheets, and carried in scrambled eggs and thin toast on a tray. She’d bring in the radio that played wartime music while we picnicked on the eiderdown and leafed through old Life magazines, imagining America. But by teatime, I was left alone while she began her panic to get supper ready in time, make sure the house was clean enough for its nightly inspection, begging me to be quiet and good. The music was taken away. Every day ended like that.

My bedtime lullaby was his voice in their bedroom next to mine as I leaned my head against my headboard and traced the outline of flowers on the wallpaper very carefully, not missing a petal or a stem, while I listened to my mother cry. If I kept tracing around the flowers, over and over, my mother would be all right. Eventually I’d fall asleep, my head crooked on the pillow, fingers drifting down the wall. But my ear still strained to catch the sound of her voice, or a sob, some clue that she still existed and would be with me in the morning. Sometimes I’d wake to dark silence and start tracing again, frantically this time, as if it would bring her back to life, rhythmically, like the machines beating in the I.C.U. After the alarm clock chimed its three rings, I’d hear movements, then voices, two of them, and I’d know that my day could begin. At night I’d call out for her over and over, wanting to be alone with her, but the footsteps that strode to my door were heavy ones. My mother was tired, my father shouted, she was busy, she couldn’t come. ‘For God’s sake, go back to sleep,’ he’d say, tucking me in too tightly. But I kept calling until their bedroom door shut and I began to trace the wallpaper flowers.

3.

When I was older I stopped calling at night and I stopped tracing the flowers, though my fingers sometimes automatically lingered over a pink rose, a violet, before I tugged the pillows over my head to shut out their voices and her crying. Most of the arguments were about me and my teenage independence. My father refused to allow me to go out at night with any friends and for a while my mother feebly tried to convince him that I should. But soon she stopped trying and pleaded with me to stop asking to go to dances or sleep-overs. I was impatient with her for letting him bulldoze her with his power and paranoia, angry because she didn’t stand up for herself, or for me. I hated her for her weakness as much as I hated him for his strength. I was ashamed of my mother for not doing what I couldn’t do: stand up to him.

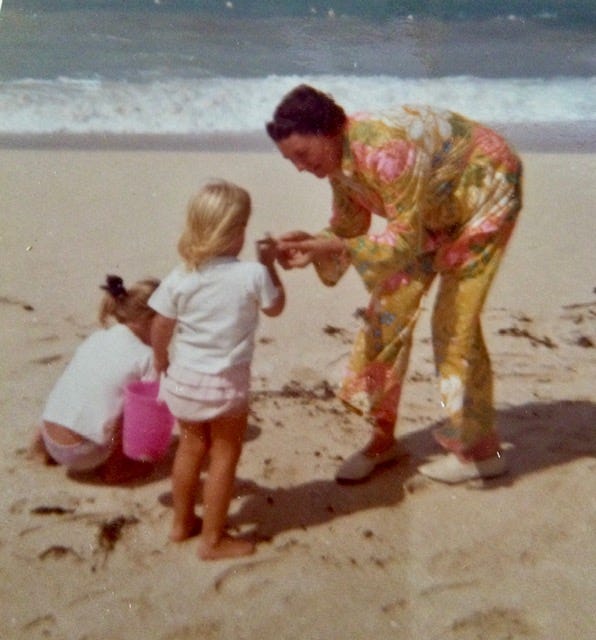

After I married, my mother, who was terrified of flying, traveled alone three times to stay with us in our homes in the tropics. We walked on sandy beaches together, swinging a toddler between us, running after another into the clear, warm water to count the fish swimming over our feet. We built castles in the sand and then, relaxing with drowsy babies, we built castles in the air with our dreams. In the spare bedroom, its windows surrounded by vines, she slept soundly, often with a baby’s arm across hers or gentle breathing against her cheek. Hibiscus bushes and trailing bougainvillea mimicked the flowers on my childhood bedroom wall. Now she was safe with me, there was no need to trace the flowers.

The first time my mother flew alone, she missed her connection in New York; my father ridiculed her on the telephone for talking to a nun and missing the announcements. My mother didn’t know about announcements so she had to spend the night in a Holiday Inn near JFK and was so frightened that she jammed her suitcase under the door handle. Fully dressed, she sat up all night, staring at the door, willing it to protect her. The second time, she tried to get on a plane for Africa instead of Jamaica, but luckily the ground staff put her on the right plane in time. The third time she arrived in red trousers. A miracle: my mother in trousers. Snapshots show her her reading to her precious grandchildren on sunny porches, her eyes bright and shining. Now she didn’t have to stop playing at the end of the day.

4.

My father wouldn’t take her to the doctor. He told me that I didn’t understand what it was like to be old, there was nothing anyone could do. He told me not to interfere. He forced her to eat, to sit and be still, to rest. She whispered to me that she felt tied down, that if she could be busy and could move around, or eat what she wanted to eat, she knew she would grow stronger. When I tried to explain, he wouldn’t listen to me either. He always knew best.

After she was finally hospitalized for tests, he found dried up sandwiches, crusty pieces of meat, crumbled cake, behind cushions, under chairs, tucked between books, but he still didn’t understand. He didn’t know that he cut out her voice while I was busy tracing the flowers on the wall, willing her back every morning to read to me again. He didn’t know that he had bound her feet and her hands, trapping her, until the only way she could get away was to die. The day before she went to hospital, she wrapped up her diaries, tightly knotting them in three plastic bags, and she threw them away. She only tore out one page to keep - the day I was born.

5.

Her eyes are closed. The nurse has pulled her curly hair, still dark, away from her forehead and tightened it into a tail that spreads out across the pillow. I had no idea it was so long. I want to wash it for her and brush it, but I let my father keep coming between us and I am only a shadow in the ICU night. One Sunday afternoon, when he and I are sitting by her hospital bed, her eyes open wide and she sits up, staring straight ahead. I lean forward to say ‘I’m here, Mom, I love you,’ but my father pushes past me to grab her left hand and hold it up, as if declaring the winner of a fight, not even cradling it next to his cheek. He says, ‘You’ve kept this ring on all these years, haven’t you?’ and before I can say a word, she sinks back into the pillow. She doesn’t open her eyes again. But late at night I tell her I love her. I tell her I’m sorry I wasn’t there for her when she needed me. And my fingers trace patterns in the still green-blue air, the colour I will always associate with my mother’s dying, instead of the transparent sea. This time my fingers don’t will her to stay - they tell her to go.

6.

My mother dies alone. After another massive stroke, she is being moved to a long-term ward care but she stops breathing in the elevator. Earlier the nurses had phoned my father to see if he wanted to accompany her to the long-term care ward but he said no. They didn’t ask me; I hadn’t made my presence strong enough when I crept in late at night, when only the night guard at the side door of the hospital recognized me. I would have held her hand while they pushed her down the hall and made sure her sheets were sweet-smelling. When she was settled I would have brushed her hair, sung wartime songs to her, talked about imagining America.

Later, the funeral home asks my father to identify her body. He refuses. He doesn’t tell me until after she is cremated and her ashes scattered by an anonymous person. My father hates funerals as much as hospitals and wants it over, quick and impersonal. I want to speak at the funeral. I want to stand up and say that I finally understand unconditional love. But my father keeps a tight grip around the flesh of my upper arm and won’t let me stand. I still let him control me. A red winged blackbird struts up and down by the glass wall behind the altar and when the minister finally blesses my mother’s body, it rises and flies away, swooping over the fields. I remember that the red winged blackbird was my mother’s favourite bird. I leave my words buried in the lilies on the top of her coffin; I return to her the words and stories she gave me years ago in the shady garden. I cannot leave her and my son has to gently pull me away.

7.

Tonight I dream in colours, brighter and lighter than I can remember in any other dream before. I am walking along a yellow sea wall and pointing across the sea towards a beach. My mother swims in the bright turquoise water beside me. She is beautiful and her black hair flows around her in the water, the way it spread on her pillow in the ICU. We are laughing and calling out to each other with strong voices. I wave to the beach where my four children - little again - are playing. The reds and greens of their hats and toys sparkle in the sun. I say, ‘Look at the children, they are so beautiful,’ and I glance down to the water. My mother has gone. The green-blue waves ruffle with diamond frills … but she has gone. I wake up with my hand on the wall behind my bed and I know she is safe.

Previously printed in my self-published poetry chapbook The Fireman’s Child (2012)

Oh Roz.... Thank you x

Oh how brave Roz. Thank you. Bev